Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his entire team deserve compliments for the grand success of India’s G20 presidency. In particular, External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar and India’s G20 Sherpa Amitabh Kant should be applauded for their months of hard work in achieving a consensus on the G20 New Delhi Leaders’ Declaration.

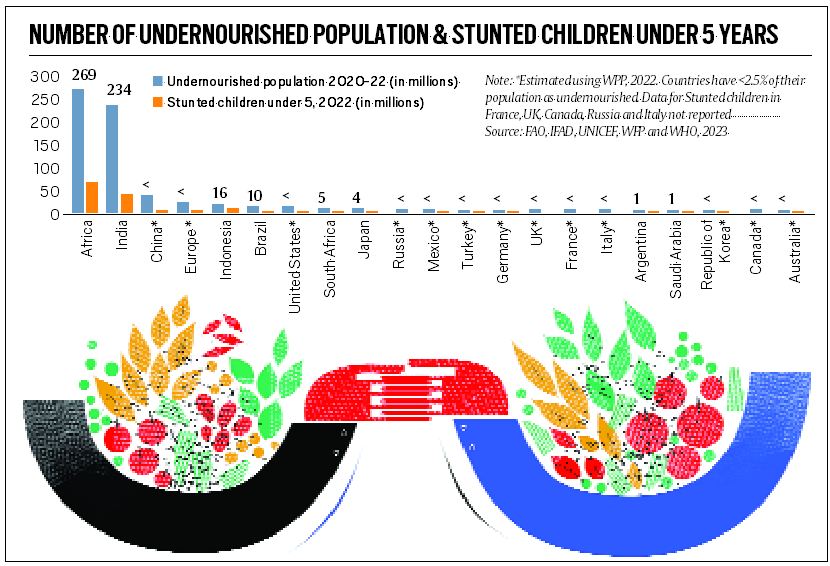

India’s G20 presidency will be remembered as a catalyst in reshaping the mindset of developed nations and integrating the aspirations of the Global South, particularly Africa, into the mainstream. India’s masterstroke with inclusion of the African Union in G20, acknowledges the significance and potential of Africa as a vital partner in global development and stability. The new G21 will now comprise of 84 per cent of the world’s population, up from about 66 per cent earlier. India and Africa, constituting 36 per cent of the global population, unfortunately, are home to nearly 69.4 per cent (503 million) of the world’s undernourished people in 2020-22. These regions together account for 67.0 per cent and 75.8 per cent of the world’s children under five afflicted with the malnutrition problems of stunting and wasting (see infographic).

The key question for the Global South is: How can it steer the world toward food and nutritional security in the face of climate change?

First, keeping international borders open for agricultural trade is the need of the hour. In this context, it is worth noting that in the last three years, India exported 85 million tonnes of cereals to the world, contributing to global food security. Against this backdrop, India’s recent restrictions on exports of rice and wheat will not go very well with G21 as it hurts the African countries the most.

Second, developed countries must commit to providing $100 billion for the loss and damage caused by climate change. This commitment will pave the way for large-scale climate mitigation and adaptation efforts in developing economies. Subsequently, the World Bank could play a catalytic role in mobilising funds even from the private sector to address the global challenges of poverty reduction, ensuring food and nutritional security and combating climate change through adaptation and mitigation policies. The G20 estimates that an additional investment of $3 trillion will be required annually through 2030 to address these issues, including debt relief for low-income countries.

World Bank President Ajay Banga has emphasised that, in addition to contributions from developed nations, private capital investments are essential to complement the current sources of financing. That is every dollar raised from developed nations should be matched with a dollar from hybrid capital and this could unlock more than $6-7 billion in lending for poorer nations to fight climate change over the course of a decade.

Third, with Africa’s inclusion in G20, the challenges posed by rapid population growth, persistent poverty, and widespread undernourishment become more serious. Initiating a comparative analysis between India and Africa could foster South-South learning and collaboration in the pursuit of sustainable agriculture and food systems. Further, addressing the abnormally high nutritional insecurity in the two regions requires agriculture policies to be more nutrition-sensitive. Scaling up bio-fortification of staple crops, an innovative and cost effective technique, can ensure availability of nutritious diets in areas affected by chronic malnutrition in India and Africa.

The Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR), with its Harvest-Plus programme, and the Indian Council for Agriculture Research (ICAR) have developed new varieties of nutrient-rich staple food crops – these include iron and zinc bio-fortified pearl millet, zinc-bio fortified rice and wheat, and iron bio-fortified beans. Such innovations can be implemented on a large-scale in Indian states and African countries to reduce malnutrition on war footing if the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of eliminating hunger and malnutrition have to be achieved by 2030.

Fourth, access to nutritious food alone cannot address the multi-dimensional problem of undernutrition in these regions. They require targeted and multi-pronged strategies to accelerate nutritional security. Our empirical analysis at ICRIER using the latest unit-level NFHS (2019-21) data (with a sample of 205,641 children under five), highlights that mothers’ education, particularly higher education (12 or more years), and mothers with normal BMI index have a strong association with reducing undernutrition among children. Between 2005-06 and 2019-21, India has reduced its percentage of underweight women (with BMI index <18.5 kg/m2) from 35.5 per cent to 18.7 per cent.

At the same time 25.9 per cent women obtain higher education today compared to 12 per cent 15 years ago. Educated women are more informed about nutrition and healthcare, tend to delay marriage, and have fewer children and healthier babies. Therefore, state governments need to promote schooling and higher education through liberal scholarship for girls. Start the scholarship with Rs 500 per month from Class 9 and increase it gradually to Rs 1,000 per month till the end of graduation and post-graduation. This can dramatically reduce dropout rates among women in secondary and higher education. Investment in women’s higher education is necessary to ensuring a significant increase in the female labour force participation and fostering long-term economic growth. These findings need to be shared widely with African nations for cross-learnings in Global South collaboration.

Most Read

Fifth, our analysis found that investments in WASH initiatives could bring about a multiplier effect on nutritional outcomes. India, under the aegis of the Swachh Bharat Abhiyan, has significantly increased the coverage of households with improved sanitation facilities from 48.5 per cent to 70 per cent between 2015-16 and 2019-21. The scheme which aimed to eliminate open defecation and eradicate manual scavenging has multiplier effects. This could be another area of learning between India and Africa to tackle the high levels of malnutrition.

The inclusion of the African Union in the G20 (now G21) is the hallmark of India’s G20 presidency. But it will have meaning only if India and Africa can collaborate effectively to deal with their food and nutrition security in the face of climate change. It is challenging, but achievable with science and open trade policies.

Gulati is Distinguished Professor and Jose is a Research Fellow at ICRIER. Views are personal

If you want to register your marriage in thane visit : https://courtmarriageregistration.co.in/court-marriage-registration-in-thane

Source link